Descendants of William Moore and Priscilla Ayers

The MOORE-AYERS line begins with

William Moore and Priscilla Ayers. William Moore,

born 6 June 1815 in Pennsylvania, was the grandson of Thomas and Eunice Bell

Moore of Greene County, Pennsylvania and the son of William and Sarah

"Nancy" Moore. William was born about 1790 in Greene County and

married his wife about 1811. Her maiden name is unknown and no marriage

record has been discovered (but it may have been Barnett, the given name of

William and Sarah's first son).

Family oral history maintains that William Moore

was accidentally killed by a horse. He and his wife had four

children: Barnett, William, Eunice Belle, and John Moore, who may have been

born a few months after his father died. William died before 16 October 1821 in

Wayne County, Ohio, where his estate was probated. His widow, Priscilla Ayers Moore, subsequently

married William Culbertson, who was appointed guardian of her

children.

Barnett apparently never married,

inherited his father's land when he came of age, and may have died at a

relatively young age. Eunice Belle Moore married William DePew, who was a

descendant of the DePew/DePuy family of New Amsterdam. John Moore married

Rebeckah Johnson.

|

|

William, the second child, married Priscilla Ayers on

January 8, 1835 in Wayne County, Ohio. Priscilla was the daughter of David Ayers (1770 - 1819) and Elizabeth Wells (1779 - 1847), and the granddaughter of Moses Ayers (c. 1732- 1803) & Dorcas Cox (1733 - 1814) and Lt. James Wells (1751 - 1826) & Rachel Letitia Leedom (1756 - 1840). According to family lore, Priscilla was a

member of a staunch Episcopalian family that was fairly well-to-do for the

time. Her family considered William beneath her, both socially and

religiously, as he was a Quaker.

According to descendant Ethel Moore, "William was a Quaker

and Grandma Priscilla was not. Grandma was pretty much of an aristocrat. Her

father, David Ayers, was a captain on a river boat on the Ohio Canal. Mr. Ayers

took a load of cargo to New Orleans and caught yellow fever and died."

Despite her family’s opposition, Priscilla and

William married and went on to have ten children together.

|

|

|

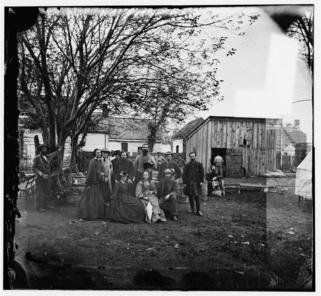

LOC Photo by James Gardner of Civil War nurses

According to Ethel Moore,

granddaughter of William and Priscilla Ayers Moore, Priscilla was a tall,

slender, and very pretty woman with dark hair and eyes. She had a beautiful

soprano voice and came from a family that was very gifted musically. Perhaps that's a gift that's passed down from generation to generation -- my mother often was asked to sing at weddings and other special occasions. I can still remember hearing my maternal grandmother's soprano voice from the church's choir loft when I was a child.

Several of Priscilla's family members also practiced medicine or nursing. Oral family history claims that one of her

nephews was an outstanding doctor who practiced medicine in a town on the Ohio

Canal. She herself was a practical nurse and it is said that two of her sisters

were Red Cross nurses during the Civil War.

|

from left: Rosalia Clayton Ruark, Cyrene Moore Clayton, and Sarah Emoline Clayton Lile

William and Priscilla Ayers Moore's

wedding ceremony took place at Priscilla's mother's home. Their eldest child, Cyrene Jeraldine Moore, was born in the home of her great-grandmother, Elizabeth

Wells Ayers (who would have been remarried by that time). After Cyrene's birth,

William and Priscilla moved to Fort Wayne, Allen County, Indiana, where they

had several additional children. Only Cyrene and Eunice Belle Moore were born

in states other than Indiana. Cyrene was born in Ohio and Eunice Belle Moore

was born in Iowa.

|

The Moores left Indiana in April

1854 to move to land on the Cedar River, close to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. In

Indiana, they had lived in an area where sentiment over slavery issues was

quite polarized, with many people favoring slavery and states' rights, and many

others staunchly opposing slavery. William Moore, a Quaker, was on the side of those advocating abolition of slavery. But was it the political climate that sparked the move?

Ethel Moore relates (from stories passed

down to her) that the main reason the Moores left Indiana was that Priscilla

Ayers Moore didn't get along with William's family.

|

The Treacherous Oregon Trail

Family history asserts that because

of his opposition to slavery and his concern over war, William Moore (the

father of several boys who would likely be made soldiers if war came) decided

to go to Oregon since it was free territory. He sold the farm in Bremer County,

Iowa and began preparations to move west in 1857. The family moved first to St.

Joseph, Missouri where wagon trains were assembled and the journey west began.

Once there, they learned of Indian troubles on the Oregon Trail, so William

Moore rented a farm at Rosehill, Missouri. There was a school in

Rosehill, where the school-age children were able to go to school.

Their eldest daughter, Cyrene, and her husband Daniel Clayton accompanied

William and Priscilla to Missouri and their first-born died in Rosehill.

Their second son was only a baby when the extended family finally left St.

Joseph by wagon train in April 1859.

|

Fifty wagons left St. Joseph.

William and Priscilla Moore had two wagons; Daniel and Cyrene Moore Clayton had

one wagon. Most of the wagons were pulled by oxen. The captain of the

wagon train was said by Moore family elders to have been unable to handle

wagon trains. After the wagon train had traveled far into the plains,

there was dissention amongst members of the group. Eventually, the problem

was solved by the group agreeing to split into two. The wagons pulled by horses

went ahead except for the two wagons owned by the Jim Giles family and the Derrick

family. Those families stayed with the wagons pulled by oxen. The reformulated

group was fairly congenial after the departure of the "horse wagon

people." The oxen and the horses were shod, as the Giles and Derrick's

horses were having problems with their hooves. Eventually, the "oxen"

portion of the original wagon train almost caught up with the "horse"

portion, which had gone ahead.

Farther along the trail, three young

men on horseback approached the wagon train and volunteered to do hunting

in exchange for being able to travel with the wagon train. These men were

Samuel Colwell, Sam's brother Frank, and John Nifong. These young men also

acted as scouts for the wagon train, reconnoitering and keeping watch for

hostile Indians. Sam Colwell was assigned to assist William Moore's wagon and

in doing so, he met young Priscilla Jane Moore, whom he later married in Walla

Walla, Washington in February 1860.

When the wagon train camped along the Sweet

Water River, every night a guard was posted to watch the livestock so it

wouldn't be stolen. The area was a good stopping place with a good place for

camping and doing laundry. A young Shoshone boy approached the wagons and

stayed around for a few days. Later he stole a mare. Determined to recover the

mare, seven men armed themselves with

the wagon train's best weapons and

rode to the Indian encampment. Someone in the group could communicate - at

least to some extent - with the Shoshones. They told the chief that a mare had

been stolen and they either wanted her returned or to have the thief turned

over to them. The unfortunate thief came sneaking into camp about this time and

the men identified him to the chief. Apparently, the young Indian was a

troublemaker even within his tribe, so the chief determined where the horse was

hidden and offered to have his son and a friend show them where the horse was.

They led them to the place and brought the horse to the rescuers. They then

accompanied the pioneers back to the wagon train. The young Native

American boys were about 12 years old and apparently had fun playing with

the children in the wagon train.

The wagon train departed after about

two days. When it reached the Platte River, the river was flooded.

The settlers propped the wagons up to the bolsters and then forced

the oxen to swim acrosss the river. Two men went through the

river with every team because the oxen were resistent. Water drenched the

insides of the wagon boxes, so the wagon train had to stop on the far side of

the river to dry out their goods and supplies.

When the wagon train reached Fort

Boise, there was only a garrison stationed there. The wagon train stopped

at the fort to learn about conditions further on. When they reached the Snake

River at about the site of present-day Vale, Oregon, they moved the wagons, people,

and goods across on rafts. By this point, it was late summer and the river was

not very high so crossing was easier than it sometimes was. No doubt it was a

much easier crossing than the Platte River adventure, because the oxen were

able to hitch a ride instead of having to swim.

After crossing the Snake River, the

wagon train followed the Burnt River Road to Emigrant Park in northeastern

Oregon. By this time, Cyrene Moore Clayton was very ill. She had only recently

given birth when the wagon trains left Missouri. Her husband Daniel

Clayton had prepared a bed in the wagon for her and the baby, but

Cyrene weakened progressively as the journey went on and by the time they

reached Oregon, all in the family feared she would die before they got to Walla

Walla.

Daniel Clayton led a cow behind their wagon and would stop and milk the

cow to have milk for the baby. William Curtis Clayton was two months old the

day the wagon train departed and was six months old the day they un-yoked the

oxen in Walla Walla, which was thought to be 15 September 1859. Thankfully,

Cyrene regained her strength and went on to have several more children,

including twins Thomas and Sarah Clayton. Sarah Emoline Clayton, called

"Emmy," was my mother's grandmother. (This information is

related from notes compiled based on personal interviews done by Estel and

Verna Lile -- my great-uncle and his wife -- of older family members

living in 1920s.)

William and Priscilla Ayers

Moore filed a homestead claim on land southeast of the city limits of present

day Walla Walla, Washington. Daniel and Cyrene Moore Clayton

also lived in Walla Walla, Washington territory at the time of

the 1860 Washington Territorial Census. In an 1867 Assessment and

Statistical Roll of Walla Walla County, Daniel was shown as having personal

property worth $750. There were 3 males and 3 females in his household.

He had three horses, four meat cattle and two hogs; 12 acres of corn, 20 acres

of wheat, 14 acres of oats, and 30 acres of barley.

By 1880, Daniel and Cyrene

Clayton homesteaded land in Columbia County (northeast of Walla Walla

County, its parent county) after living near Walla Walla for many years.

Cyrene's parents William and Priscilla Moore sold their land in Walla Walla

County and moved to Columbia County as well. Their son-in-law Daniel Clayton died in 1902 in Pomeroy, Garfield

County, Washington. Cyrene Moore Clayton died January 17, 1917 in Asotin

County, Washington.

For

more information, see:

Moore, Carl C. and Dorothy L. Descendants of William Moore. Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Washington - ISBN

0-87770-322-1, (c) 1984; see also: Luther, Ellen (Betty). Ancestors

and Descendants.

Self-published 1998. (Contains history of Moore, Ayers, Cox, Rockhill,

and related families). .

|

William died in Columbia

County on January 31, 1885 and is buried in the Turner Cemetery.

Priscilla

Ayers Moore died in Prescott, Walla Walla County, Washington on March 8,

1896. She was buried next to her husband in the Turner Cemetery in Columbia

County.

|

|

|